Lure of the Mills...

Between 1840 and 1930 roughly 900,000 French Canadians left Canada to emigrate to the United States. However, roughly half of them would return to their homeland after one or several stays.

In many ways these people could be considered migrant workers at a time when access to work was simply a day's journey away by train, an opportunity to earn some cash to return home with... to pay off debts... to buy a small farm. Since leaving everything and everyone known to you can be wrenching, or even too jarring to imagine, for a lot of these good folks the idea of permanently staying in New England was never utmost in their minds. England. English. No, they would stay just long enough to make sufficient money to jumpstart their lives back home.

So, they poured into New England in droves. Entire families consisting of parents with over a half dozen children, most often without an English word among them, were met at train depots throughout the area by kin who arrived months, maybe a year, before. Jobs were waiting for them--even the children down to the eight or ten year olds could be employed somehow. As seasons turned into years, many with the best intentions of returning to Québec never found their way back.

But why leave Québec anyway?

Why leave family and countryside for mill towns with their rows of crowded, noisy tenements housing multiple families, sun-up to sun-down work hours amidst dangerous and deafening machinery, and a weekly pay that really wasn't that great.

The reason why, simply put, is that the farms of Québec could no longer support the population. Hunger was the wolf howling in the night. Between 1784 and 1844, Québec's population increased by about 400%, while its total area of agricultural acreage rose only by 275%, creating an important deficit of available farmland. Hence, there were thousands of landless farmers searching for a way to feed a family, whether it be subsistence farming or working in the woods felling trees for the timber barons. Trying to squeeze a turnip out of worn-out farmland, or harvesting trees can be hard labor, indeed. The hours were long and the pay wasn't so great.

So, the truth is that life for some folks is not a picnic anywhere. Neither here nor there. Just different. So what was the nudge? Well, it wasn't the six months of winter for they had adapted to that weather pattern long ago, nor was it a government that made them feel somewhat unappreciated, that had been a reality since 1760. Being seen as stubborn, ill-educated farmers with too many children, speaking a language more appropriate to the 18th century, a patois that had gotten a bit ragged over the last hundred years, was nothing new. An oddity in their ways. Adhering to a mystical religiion. All that, too. However, everything aside, there still needed to be something to shove them out the door. Enticements.

Of course. Some of the enticements were in the form of hiring agents sent out by New England's thriving mills, other lures came from relatives who had already made the trip and returned to the old farm sporting new clothes or a shiny new pocket watch. Or a letter similar this: The pay is good, Basile. We work from sunrise to sunset, but on Sunday the mills are closed and it is like a church holy day. The work is not hard. I am in the cotton mill. Some of the children are working and we make more money than we can spend. Let me know what you decide, and if you want to come I will speak to the foreman.

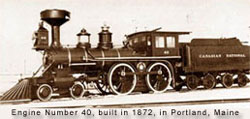

A compelling nudge could well have been the newly-laid tracks of a railroad, the Passumpsic perhaps, that would bring them down to the States and back... or maybe not back. At least there could be a return trip, a possible reversal of a bad decision always makes a decision easier to make, after all.

A one-way ticket from Montreal to Fall River on the Passumpsic Railroad was only about $10. That measured against the wages of $1 a day for a carder in a Fall River mill meant it was two weeks pay, or four weeks if one had room and board obligations, or much longer is one had a young family and owed most of what he earned to the company store.

But alas, not everyone welcomed or even appreciated this new labor source, to wit the 1880 state labor commissioner of Massachusetts, Carroll B. Wright, who wrote this in his annual report: With some exceptions the Canadian French are the Chinese of the Eastern States. They are a horde of industrial invaders, not a stream of stable settlers. These people have one good trait. They are indefatigable workers and docile. To earn all they can be no matter how many hours of toil... and to take out of the country what they can save: this is the aim of the Canadian French in our factory districts.

Admittedly, there is more than a hint of truth in the good commissioner's assessment even if he could have stated it in a more civil way.

Repatriement. Repatriation. At first the Québec elite (they were not all farmers, after all) didn't miss their down-on-their-luck neighbors leaving Canada for the States. Not until areas began to be noticeably depopulated, churches were half empty and young labor had gone south... often to stay, did the Québec elite come to the idea that they might have a national calamity on their hands. This was around 1870, which by then a generation of Franco-Americans had been born. Difficult to put that genie back in the bottle. Nevertheless, an all out effort called Repatriation was initiated to entice back to Québec the French Canadians who had left their homeland.

Repatriement. Repatriation. At first the Québec elite (they were not all farmers, after all) didn't miss their down-on-their-luck neighbors leaving Canada for the States. Not until areas began to be noticeably depopulated, churches were half empty and young labor had gone south... often to stay, did the Québec elite come to the idea that they might have a national calamity on their hands. This was around 1870, which by then a generation of Franco-Americans had been born. Difficult to put that genie back in the bottle. Nevertheless, an all out effort called Repatriation was initiated to entice back to Québec the French Canadians who had left their homeland.

To accomplish this repatriation, the powers that were, decided to send a large number of priests, nuns and brothers to the area to ensure that the immigrants would keep their language and their faith in the meantime. This is the start of where you see in mill towns throughout New England the building of churches devoted to French-speaking parishioners with French-speaking priests. Attached to these churches were often parochial schools where French was taught by French-speaking nuns and brothers. All the while, the immigrants were encouraged to return to Canada with promises of land and loans. Some did. Most didn't.

Along with the French clergy that were arriving, there were French Canadian professionals: doctors, dentists, pharmacists, lawyers and merchants who saw opportunities for profit. Together, clergy, professionals and immigrants established 'petits Canadas' (Little Canadas) where a person could live their day-to-day existence without ever needing to speak English or to ever assimilate. Why return to Québec when they had Québec right here. Although the concept of Little Canada would be short lived, those who were here didn't realize it. Obviously, Repatriation didn't work because Canadians continued to stream into New England at least until 1873.

From 1873 to 1878, there was a severe depression in the United States which caused massive layoffs in the textile industry. This was followed by other downturns in 1891, and again from 1894 to 1896. Then there was a generation of prosperity from 1896 to about 1913. By this time, however, the big push out of Canada was over, and those French Canadians who were here were well established.

Of the group that eventually remained in the States, a tiny handful of ten Canadian-born adults to be exact, would become my ancestors. Some made the trip twice to the States before settling in, for others it was always meant to be a one-way trip.

Collectively, these good folks brought an estimated 20 children with them. All were farmers or the children of farmers, and they arrived in New England roughly between 1860 and 1896. Some came from villages south of Montreal, another like my father's mother came from a region known as the Gaspé Peninsula where the St. Lawrence River is wide and the waters are beginning to mix with that of the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

***

This is the roster of the above mentioned, my ancestors and ancestors to countless others, easily several thousand spread out across the United States, but most remaining in New England:

Louis Fournier and his wife Marie Dore and their three daughters left Rouville County in the early 1860's and were known to be in Vermont in 1862 where a fourth daughter was born in August.

Zoel Turcotte and his wife Caroline Campagnas and at least six of their children left Arthabaska County for the first time in 1879 to settle in Lewiston, Maine.

Antoine Dargie and his wife Helene LaFond and possibly six of their children left Arthabaska County in 1873 to settle in Lewiston, Maine.

Ernest Camirand, a bachelor from St. Maurice County arrived in Attleboro, MA in 1881.

Louis Lizotte and his wife Adelaide Page and possibly four of their children left St. Maurice County in 1880 to settle in Fall River, MA.

Celina Senechal, a single young woman of 17 years old, left Matapedia County for the first time around 1896 to settle in Fall River, MA..

These individuals, unknown to one another in Canada, became the foundation of a very large family.

A street scene of a Canadian village painted in 1829.

Back of the Durfee Mill in Fall River, MA taken in 1916.

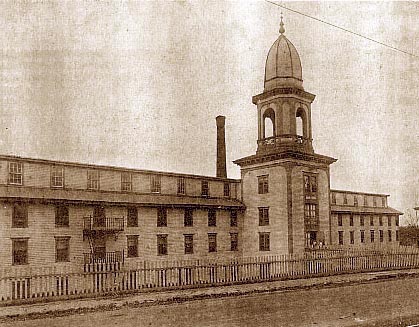

Photo of the Dodgeville Mill in Attleboro, MA, c. 1900. The building is now owned by a descendent of two of those who made the trip.

Sources used: An article written by Claude Belanger of the Department of History at Marianopolis College in Montreal, dated 8-23-2000, entitled French Canadian Emigration to the United States 1840-1930.

A booklet, "The French in Rhode Island"edited by Albert K. Aubin and published jointly by the R.I. Heritage Commission and the R.I. Publications Society in Providence 1988.

According to the 1980 American census, 13.6 million Americans claimed to have French ancestors. While a certain number of these people may be of French, Belgian, Swiss, Cajun or Huguenot ancestry, it is certain that a large proportion would have ancestors who emigrated from French Canada or Acadia during the 19th and 20th centuries. ... Claude Belanger.

Note: The history of this family group, which is essentially the story of the half million French Canadians who made New England their forever home, continues on a separate site, currently under construction, entitled The Lure of the Mills.